Gantry Rotation vs Specimen Rotation

GANTRY ROTATION vs. SPECIMEN ROTATION:

IMPLICATIONS FOR IN VIVO IMAGING

Introduction

In computed tomography (CT) and related imaging modalities, projection data for reconstructioncan be acquired by either rotating the gantry around a stationary subject or rotating the subject infront of a fixed source–detector pair. From a purely geometric and mathematical standpoint, thesetwo approaches are equivalent—assuming a rigid object and a perfectly calibrated system.

However, when applied to in vivo imaging of living animals, which are inherently non-rigidand subject to motion and deformation, the equivalence breaks down. Both published studiesand current market systems indicate that biological motion, mechanical stability, and practicalconsiderations all favor gantry rotation as the method of choice. Along with patient comfort, this isthe key reason why clinical linear accelerators only employ gantry rotation.

System Design and Application Domain

Most in vivo small-animal CT systems employ a rotating gantry with a stationary bed. This configuration:

- Minimizes physical stress on the animal.

- Maintains stable anesthesia, monitoring, and catheterization lines.

- Reduces motion artefacts caused by physiological processes, like respiration or cardiac activity.

- Simplifies monitoring during scans, ensuring uninterrupted access to support systems (IV lines,ECG, breathing, body temperature control).

- Reduces the impact of X-ray scatter on image quality, particularly along the long axis of theanimal, improving contrast and spatial resolution in projection data.

During in vivo imaging, multiple support systems are required, such as intravenous lines, respiratoryassistance, and physiological monitoring (ECG, breathing, body temperature). By keeping the animalon a stationary bed, these connections remain stable and accessible, preventing torsion of cablesand ensuring consistent anesthesia and monitoring throughout the scan.

Mechanical Stability and Calibration

Rotating specimen stages demand precise alignment of the rotational axis to minimize eccentricity and wobble, both of which may generate ring or streak artifacts. Additionally, rotating beds require motors and transmission systems that can introduce micro-vibrations or resonances within the animal.

In contrast, rotating gantries primarily require mechanical stability of the source–detector assembly, which is more easily maintained through routine calibration. Gantry rotation, particularlywhen physically separated from the bed, as in the SmART+ (Small Animal RadioTherapy) preclinicalirradiator (Precision X-Ray, Inc., Madison, CT), causes minimal disturbance and reduces mechanicalvibrations in the animal, consequently improving signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) reconstruction quality.

Reduction of Deformation and Motion Artifacts

Animal rotation can introduce soft-tissue deformation through centrifugal forces, imperfectfixation, or micro-vibrations of the stage. Such effects can manifest as blurring, rings, or streakartifacts in reconstructions. By keeping the subject stationary, these sources of distortion arelargely avoided, leading to more reliable anatomical and functional imaging.

Practical Considerations

For live animal studies, rotating the gantry is safer and more practical:

- Prevents torsion or tangling of anesthesia and monitoring lines.

- Reduces risk of stress or injury to the subject.

Clinical Relevance

The choice between gantry and specimen rotation is not only important in preclinical researchbut also highly relevant to clinical practice. In human CT imaging, gantry rotation is universallyadopted for many of the same reasons observed in animal studies:

Translational continuity: Using gantry-based imaging in preclinical systems mirrors the clinicalstandard, ensuring that animal imaging protocols, artefact characteristics, and reconstructionstrategies closely align with those used in patient care. This strengthens the translational bridgebetween preclinical findings and clinical applications.

Workflow efficiency: Gantry rotation supports faster setup, easier positioning, and integration ofmultimodal imaging—all of which are essential in both preclinical and clinical environments.

Minimized motion artefacts: Keeping the patient stationery reduces the possibility ofmisalignment during image capture, which is critical for high-quality diagnostic imaging.

Patient comfort and safety: Just as small animals require stable anesthesia lines, human patientsrequire stable IV access, ventilators, ECG leads, and monitoring devices during imaging. A rotatingbed could compromise these connections and pose risks.

By adopting gantry rotation in small-animal imaging, researchers not only optimize image qualityand animal welfare but also ensure methodological continuity with clinical imaging practices,enhancing the translational impact of their work.

Summary

While gantry and specimen rotation may be mathematically equivalent in theory, they are notinterchangeable in practice for in vivo imaging. Gantry rotation provides superior stability, reducesartifacts, and ensures animal safety by minimizing stress and preserving physiological monitoring.For these reasons, rotating gantry designs are the established standard in both commercial smallanimal imaging systems and published preclinical studies.

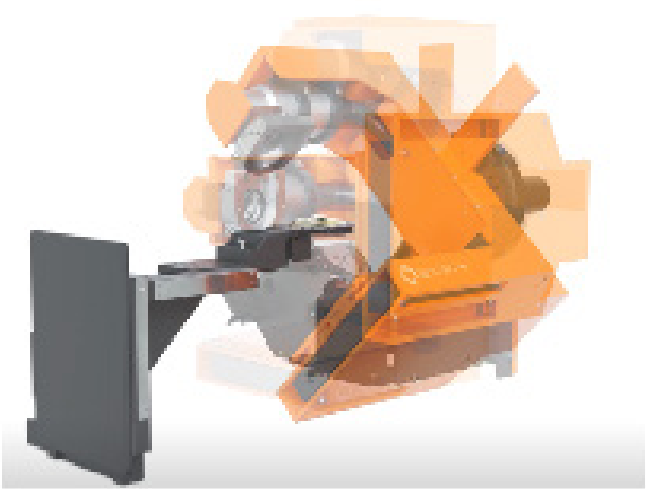

Figure 1. ROTATING GANTRY SmART+ (Small Animal Radiotherapy System), Precision X-Ray, Inc.(Madison, CT, USA). On the left, the gantry (orange) is shown with the X-ray tube positioned above and thedetector below the specimen at the initial 0° angle. On the right, the gantry rotates around the specimen,which remains immobile at the center.

References

Dillenseger, J. P., Goetz, C., Sayeh, A., Healy, C., Duluc, I., Freund, J. N., … & Choquet, P. (2017).Estimation of subject coregistration errors during multimodal preclinical imaging using separateinstruments: origins and avoidance of artifacts. Journal of Medical Imaging, 4(3), 035503-035503.

Hsieh, J. (2024). Spatial and temporal motion characterization for x-ray CT. Medical Physics, 51(7),4607-4621.

Kyme, A. Z., & Fulton, R. R. (2021). Motion estimation and correction in SPECT, PET and CT. Physicsin Medicine & Biology, 66(18), 18TR02.

Nardi, C., Molteni, R., Lorini, C., Taliani, G. G., Matteuzzi, B., Mazzoni, E., & Colagrande, S. (2016).Motion artefacts in cone beam CT: an in vitro study about the effects on the images. The Britishjournal of radiology, 89(1058), 20150687.